Mudface

-

Posts

12,445 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Articles

Forums

Store

Posts posted by Mudface

-

-

6 minutes ago, Dougie Do'ins said:

Coronavirus: Satellite traffic images may suggest virus hit Wuhan earlier

That's erm, a tad tenuous.

-

There were 324 deaths and 1600-odd new infections reported last Tuesday. It's still coming down but pretty slowly.

-

15 minutes ago, Rotpeter said:

Klopp has mentioned the situation with him a couple of times. It sounds like his body can't handle our levels of intensity.

Wow, that's probably the last thing you'd expect, he's built like a brick shithouse. A little one like, but still.

-

8 hours ago, dockers_strike said:

Xherdhan Shaqiri is another who will depart with Newcastle keen on signing the Switzerland international. He, however, will command a substantial fee.

Real shame about Shaqiri. I wonder why he's been sidelined so much, he's looked pretty good whenever he's played and seems to have a good attitude.

-

I never particularly found any of them all that attractive. The ginger one had nice tits though.

-

1 hour ago, cloggypop said:

Mudhoney facemasks available here

Touch me, I'm sick.

-

2

2

-

-

Just now, TheHowieLama said:

There will not be another lockdown unless/until the second wave becomes worse than the first.

Western Governments have all accepted certain stats as ok and painted them as "winning".

In the US that means less than 25k new cases and less than 1000 dead - a day.

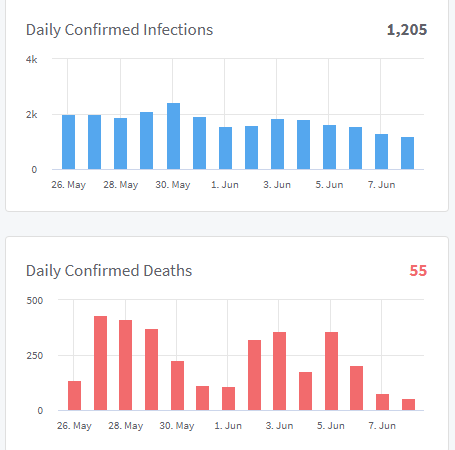

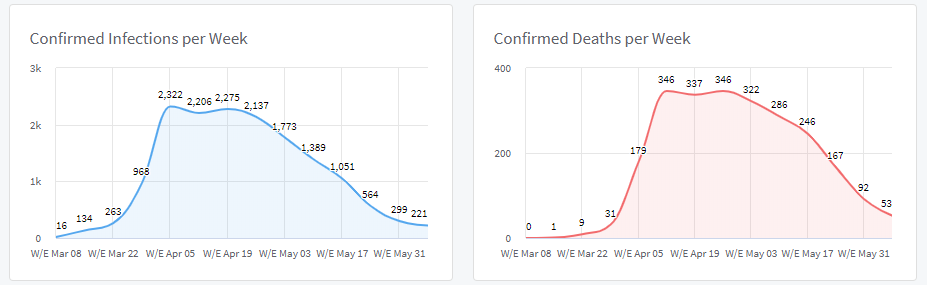

In the UK it is less than 2000 new cases and less than 200 dead - a day.

Sadly you're probably right. All that guff about local lockdowns is just that, they've got no real intention of doing anything of the sort. Fortunately, I live in Scotland these days and Sturgeon seems to have both the autonomy and the will to do it 'right'.

-

1

1

-

-

21 minutes ago, Stickman said:

Never fucking heard of them...Cazoo that is not Everton

I was gonna say they're a small time club that wear blue shirts and play in the European and prospective Premier League champion's city, but sounds like you know.

-

2 minutes ago, S.i.t.M aka The Boring One™ said:

So if we see a low number tomorrow, perhaps we have grinder through the worst of it. Hopefully light at the end of the tunnel.

The figures invariably go up after the weekend, the number should be higher but hopefully a lot lower than last Tuesday. We're clearly through the worst of the first phase, but the new infection rate is still very high, especially in England. With the recent easing, and the track and trace looking like the usual Tory outsourcing cluster fuck, it's still a big worry that a second wave could get sparked off and we'd be unable to control it without a further lockdown.

-

7 minutes ago, S.i.t.M aka The Boring One™ said:

Where are you seeing 111? BBC website says 55 as does coronavstats website.

1 minute ago, TheHowieLama said:He is talking about last Monday

Yep. From the chart here- https://coronavstats.co.uk/uk. If you hover over the bars, you can see figures for previous days.

-

1 minute ago, Spy Bee said:

Only 55 deaths nationwide today and the infection rate is the lowest for ages. That's a huge drop onlike for like days. I think it was 294 last Monday.

It was 111, but there's always a big jump on Tue/ Wed, last week there were well over 300 deaths on both those days. Encouraging though, just wish the infection figures would come down more quickly. 1200- 1500 per day is still pretty high.

-

It's moronic, they've got the worst of both worlds, lockdown was too late, and easing far too early.

-

1

1

-

-

Must be a pisser spending £87 million on a house, then having to cough up another £65 million on snagging.

-

1

1

-

-

No new deaths in Scotland for the second day running. There'll be the weekend lag, but some rare good news for once.

-

56 minutes ago, Scott_M said:

Although obviously a daft idea on paper, I was watching a couple of German games yesterday with the fake crowd noises & I have to admit, it was significantly better than I thought.

My concern with the noises in the Premiership, is that it’s a different type of atmosphere. In Germany, a lot of the atmosphere is a white noise of constant chanting that doesn’t always coincide the action on the pitch, whereas the atmosphere in the Premiership is more reactive to the action on the pitch.

There better be a stock 'Since 1995' chant to broadcast.

-

1

1

-

-

2 minutes ago, Bobby Hundreds said:

Probably end up with a private corporate police force. The thought of it terrifies me.

Serco PD. Minimum wage kids given ten minutes of training and a badge, then shoved on the streets.

-

1 minute ago, Spy Bee said:

I live in that region. Betsi accounts for 25% of the entire population and it was late to get any decent level of testing going on. Also, a nursing home not far from us had 26 out of 31 residents test poisitive. I believe in the Denbighshire and Conwy areas, they had similar hotspots. Per capita Betsi is doing okay really, but then it should do because of the whole it's quite rural and relatively spares compares to South Wales.

Yeah, my Mum and aunt and uncle live near Mold and we grew up in Prestatyn. It's a big area.

-

Just now, Spy Bee said:

The UK had far and away it's best day since the peak of this crisis yesterday, and we still came 8th on the most deaths table. Of thos above us, only Chile and Peru have smaller populations.

And it was a Sunday as well, we'll get the usual bump today and tomorrow no doubt.

Scotland seems to be doing pretty well, almost 50% reductions in deaths and infections for a few weeks, and about 25% last week.

Wales looks to have a bit of a hotspot around the Betsi Cadwalladr area, but there's big reductions in infections over the last fortnight, so hopefully that'll continue.

-

Fucking moron. Lucky he didn't end up getting lynched.

-

New Zealand appear to have eliminated the virus and are to remove all restriction except border controls. If only we had a competent government here, we could be doing the same but no, we're still getting more infections each day than NZ have had in total.

A couple of public health experts make some recommendations to keep the virus eliminated here- https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2020/jun/08/five-ways-new-zealand-can-keep-covid-19-cases-at-zero

Five ways New Zealand can keep Covid-19 cases at zero

Modelling shows it is very likely New Zealand has eliminated coronavirus. Keeping it that way is the next big challenge

Michael Baker and Nick Wilson

Today, for the first time since 28 February, New Zealand has no active cases of Covid-19.

According to our modelling at the the University of Otago, it is now very likely (well above a 95% chance) New Zealand has completely eliminated the virus. This is in line with modelling by our colleagues at Te Pūnaha Matatini (a research centre based at University of Auckland).

It is also the 17th day since the last new case was reported. New Zealand has a total of 1,154 confirmed cases (combined total of confirmed and probable cases is 1,504) and 22 people have died.

Today’s news is an important milestone and a time to celebrate. But as we continue to rebuild the economy, there are several challenges ahead if New Zealand wants to retain its Covid-19-free status while the pandemic continues elsewhere.

It remains important that good science supports the government’s risk assessment and management. Below, we recommend several ways people can protect themselves. But we also argue New Zealand needs an urgent overhaul of the health system, including the establishment of a new national public health agency for disease prevention and control.

What elimination means

Elimination is defined as the absence of a disease at a national or regional level. Eradication refers to its global extinction (as with smallpox).

Elimination requires a high-performing surveillance system to provide assurance that, should border control fail, any new cases would be quickly found. Agreed definitions are important for public reassurance and as a basis for expanding travel links with other countries that have also achieved elimination.

It is important to remind ourselves that active cases are not the ones we need to worry about. By definition, they have all been identified and placed in isolation and are very unlikely to infect others. The real target of elimination is to stop the unseen cases silently spreading in the community. This is why we need mathematical modelling to tell us that elimination is likely.

Avoiding complacency – and new outbreaks

New Zealand’s decisive elimination strategy appears to have succeeded, but it is easy to become complacent. Many other countries pursuing a containment approach have had new outbreaks, notably Singapore, South Korea and Australia.

New Zealand has spent months expanding its capacities to eliminate Covid-19. But maintaining elimination will be challenging. Airports, seaports and quarantine facilities remain potential sites of transmission from overseas, particularly given the pressure to increase numbers of arrivals.

New Zealand’s move to alert level 1 will end all physical distancing restrictions. If the virus is reintroduced, this creates the potential for outbreaks arising from indoor social gatherings. New Zealand is also moving into winter when respiratory viruses can spread more easily, as is seen with the highly seasonal coronaviruses that cause the common cold.

Just as New Zealand prepared for the pandemic, the post-elimination period requires “maximum proactivity”. Here are five key risk management approaches to achieve lasting protection for New Zealand against Covid-19 and other serious public health threats.

1. Establish public use of fabric face masks in specific settings

Health protection relies on multiple barriers to infection or contamination. This is the cornerstone of protecting drinking water, food safety and borders from incursions by biological agents.

With the end of physical distancing, we recommend the government seriously considers making mask wearing mandatory on public transport, on aircraft and at border control and quarantine facilities. Other personal hygiene measures (staying home if sick, washing hands, coughing into elbows) are insufficient when transmission is often from people who appear well and can spread the virus simply by breathing and talking.

The evidence base for the effectiveness of even simple fabric face masks is now strong, according to a recent systematic review published in the Lancet. The World Health Organization has also updated its guidelines to recommend that everyone wear fabric face masks in public areas where there is a risk of transmission. Establishing a culture of using face masks in specific settings in New Zealand will make it easier to expand their use if required in future outbreaks.

2. Improve contact-tracing effectiveness with suitable digital tools

New Zealand’s national system for contact tracing remains a critical back-stop measure to control outbreaks, should border controls fail. But there is significant potential for new digital tools to enhance current processes, albeit with appropriate privacy safeguards built in. To be effective, such digital solutions must have high uptake and support very rapid contact tracing. Downloadable apps appear insufficient and both New Zealand and Singapore are investigating bluetooth-enabled devices which appear to perform better and could be distributed to all residents.

3. Apply a science-based approach to border management

A cautious return to higher levels of inbound and outbound travel is important for economic and humanitarian reasons, but we need to assess the risk carefully. This opening up includes two very different processes. One is a broadening of the current categories of people permitted to enter New Zealand beyond residents, their families and a small number of others. This will typically require the continuation of routine 14-day quarantine, until improved methods are developed.

The other potential expansion is quarantine-free entry, which will be safest from countries that meet similar elimination targets. This process could begin with Pacific Island nations free of Covid-19, notably Samoa and Tonga. It should be possible to extend this arrangement to various Australian states and other jurisdictions such as Fiji and Taiwan when they confirm their elimination status.

4. Establish a dedicated national public health agency

Even before Covid-19 hit New Zealand, it was clear our national public health infrastructure was failing after decades of neglect, fragmentation and erosion. Prominent examples of system failure include the Havelock North campylobacter outbreak in 2016 and the prolonged measles epidemic in 2019. The comprehensive health and disability system review report was delivered to the Minister of Health in March and was widely expected to recommend significant upgrading of public health capacity. This report and its recommendations should now be released.

We also recommend an interim evaluation of the public health response to Covid-19 now, rather than after the pandemic. These reviews would inform the needed upgrade of New Zealand’s public health capacity to manage the ongoing pandemic response and to prepare the country for other serious health threats. A key improvement would be a dedicated national public health agency to lead disease control and prevention. Such an agency could help avoid the need for lockdowns by early detection and action in response to emerging infectious disease threats, as achieved by Taiwan during the current pandemic.

5. Commit to transformational change to avoid major global threats

Covid-19 is having devastating health and social impacts globally. Even if it is brought under control with a vaccine or antivirals, other major health threats remain, including climate change, loss of biological diversity and existential threats (for example, pandemics arising from developments in synthetic biology). These threats need urgent attention. The recovery from lockdown provides an opportunity for a sustained transformation of our economy that addresses wider health, environmental and social goals.

Michael Baker and Nick Wilson are professors of public heath at the University of Otago -

14 minutes ago, Jairzinho said:

Which way's the ball going?

-

10 minutes ago, Section_31 said:

The JK Rowling stuff is illuminating in a number of ways.

The first is that it's gaslighting pure and simple. She expresses an opinion and is immediately flamed (isn't that what they call a Twitter pile on?). The gist seemingly being "she has a platform which she could talk about so much stuff yet chooses to talk about this!", the notion being that she's not allowed to, and if she does she'll be hammered for it. Ironically that's the kind of stuff a lot of these folks bemoan Trump and Johnson's acolytes for.

The second is that it's a clash of ideologies between people who feel downtrodden. Rowling was a single mum who grew up in Thatcher's Britain and so probably has strong views about it. She probably feels aggrieved that under the present rules of engagement, she could be vaving a gathering of the Edinburgh women's rights association and Bill Clinton could walk in still smelling of intern juices, play some Kenny G, then announce how good it is to be in the presence of so many fellow longsuffering sisters.

Third, there's like a clash of fame cultures going on too I reckon. A lot of the blue tick brigade are jealous because her fame comes from a time when people were famous for being good at things, not for vlogging about how depressed they're feeling today and it was only the love of the subscribers that get them through the day. I mean fucking hell, imagine being the world's richest author and being told your books are shite by someone that works at Cafe Nero.

Some of these people are every bit as destructive to public discourse as the people they claim to hate. Stifling debate is one of the drivers of populism, they feed off each other like some kind of modern, twisted version of the military industrial complex. You could see it starting years ago when you'd get identikit politicians like Clegg and Blair and David Miliband and someone would ask about immigration and they'd stiffen up and be like "yeah it's great immigration, immigration for all." Then the only other opinion that didn't jive would be an extremist one like the BNP or Farage, which was BNP in a fur coat. There was never anywhere for the middle of the road opinions to go, it was always either "all immigration is great, there should be no room for any fear/concerns/debate and if you dont agree you're racist." Or "all immigration is bad, they should go back to Bongo bongo land."

It's the same with this now. People often feel they either have to stay out of it completely for fear of being branded all manner of bigot, or find a home with the only person saying they agree with you, but who are sadly usually people with extremist views on other subjects.

The most ridiculous thing about all this, is that you have feminists fighting with trans-people. The 'right' must be laughing their asses off.

-

Wasn't sure where to post this, so here'll do- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/06/everyone-is-in-that-fine-line-between-death-and-life-inside-everests-deadliest-queue

A thoroughly depressing article which seems to sum current humanity up perfectly.

'Everyone is in that fine line between death and life': inside Everest's deadliest queue

A year on from the loss of 11 people on the world’s highest mountain, survivors talk about what went wrong and why

Nirmal Purja is someone who responds to a crisis by becoming completely calm. When the Nepalese mountaineer saw the line of about 100 people waiting to reach the crest of Everest on 22 May last year, he knew there was no way he could overtake the slower climbers. Mentally, he abandoned the record he was attempting, for the fastest climb between the neighbouring peaks of Lhotse and Everest.

Poor weather at the start of the climbing season had meant there was only a very small window of time in which people could attempt the summit – just three clear days. In 2018, the year before, there had been 11 good days, allowing climbing companies to stagger their teams. Purja had known there would be queues, but was taken aback by the numbers.

Purja, a 36-year-old veteran of the Royal Navy’s elite Special Boat Service, has climbed Everest four times, and was philosophical. “It is what it is. I always try to stay calm on the mountain,” he tells me, speaking from his home in Winchester. In normal circumstances, he would have been up Everest this year, but he is defusing the frustrations of lockdown by writing a book about climbing all 14 of the world’s highest mountains in just 189 days last year.

Summits can be a disappointment when you see that number of people taking selfies in such a spiritual place

He took a picture of the queue at the top of Everest, which he later posted on Instagram, mainly as an explanation to his sponsors and supporters – a vivid image of the obstacle that had slowed him down. Then he tried to assess how he could help. He knew things could go catastrophically wrong, and quickly; this stretch of Everest, from the sheer rockface of the Hillary Step to the summit, was the most exposed part of the climb, with drops of up to 3,000 metres (9,842ft) on either side. As people queued, they got colder and used up unplanned-for quantities of their oxygen supplies. It was literally the worst place on Earth to get stuck in a queue.

Looking at the line, with climbers travelling in both directions, Purja realised it would be impossible to rescue anyone who needed to be taken off the summit fast. Every climber was clipped to a safety rope, and the path is too narrow to allow the more experienced climbers to unclip and pass the slower climbers. The queue continued to build. Purja couldn’t be confident that other climbers would be helpful in an emergency. “If you have to drag a body through that, no one would be able to give up the path to them. There is no path, and people are in their own survival state at that altitude, struggling to put one foot in front of another. Everyone is in that fine line between death and life.”

Nirmal Purja at the summit of Everest summit in May 2019.

FacebookTwitterPinterest

Nirmal Purja at the summit of Everest in May 2019. Photograph: published with permission of Nirmal Purja

Purja paused at Hillary Step and tried to quell flaring tensions between climbers; there were arguments about whether the people trying to get to the summit should be given priority over those trying to descend. “I managed the queue for two hours. Rather than people fighting over who should go up first, it’s better if it is managed systematically,” he says. He worked out who had been waiting in critically cold conditions for the longest and prioritised them, and tried to calm the other climbers, taking off his mask to issue instructions.

Purja’s experience and military background meant that climbers were happy to be guided by him. Elsewhere, local Nepalese guides were finding it harder to convince their clients that they needed to turn back. There was a dangerous clash between the typically alpha-plus personalities of people who want to summit Everest and their guides, who are dependent on their fees for survival.

“When people are in stressful situations, they do shout,” Purja says. “You can only get a few words out at that altitude: ‘Move faster! Come off!’ I disagree with it, but people come to Everest carrying a huge financial burden. Not only that, but they have spent more than two months and a lot of effort to be ready. That’s why everybody rushes for the top.”

A year on, Thomas Becker tells me he remains disturbed by the behaviour he witnessed while queueing to reach the highest place on Earth. He is a lifelong climber, although it was his first attempt at Everest. He describes the experience as being “very Lord Of The Flies”. At the worst part of the queue, he was stuck in a line of around 40 climbers, behind a woman who was struggling. He had never met her and didn’t know her name, but was worried by how inexperienced she seemed, unable to use her ice axe. He spent several hours helping her, so that he could shuffle forward himself, patiently advising her where to put her feet and catching her when she slipped. Behind them, tempers began to fray and climbers started swearing: “Fucking get moving!”, “Get the fuck off here!”, “What the fuck are you doing?”

Becker, a former rock guitarist who teaches human rights law at Harvard, was startled by the ruthlessness of his fellow climbers. Earlier in the day, he had discovered that someone had stolen eight of the oxygen tanks his team had stashed by their tents at base camp, which meant he was climbing the most dangerous stretch of the mountain with just two canisters instead of six. The theft was “disappointing”, he says now, with polite understatement. “There is a code of ethics on the mountain that you don’t steal anyone else’s oxygen, because it could be fatal.” He was also puzzled. “This is not the norm. Sometimes, someone might take one to stay alive, but to have a big chunk of tanks stolen... The folks we were with said this was the first time they had ever seen anything like that.”

He managed to feel a brief sense of elation as he embarked on the final stretch, edging closer to an ambition he had held since reading about Everest as a child. But it was a fleeting sensation. “It became less exciting when we started to see people being brought down, dead bodies. It became sad quickly.” By the time he got to the summit, he had walked past a number of corpses. “Just 10 minutes shy of Hillary Step, there was a guy attached to a rope who had passed away, dangling there. I think I saw five bodies that day, six maybe. There are people literally lying in your path, frozen,” he says. “It’s brutal.”

There are people who call up and ask: ‘I’ve never climbed anything. Can I go with your company? And I need a discount’

Purja’s startling images of the queue at the top of Everest quickly went round the world. People who know nothing about mountaineering were shocked by this contradiction between the mountain’s reputation as a lonely and unattainable peak, and the banal reality of a rush-hour crush. But it was more than banal: 11 people died on Everest that May, more than twice the number of climbers who had perished the previous year – a figure widely attributed to the crowded conditions and the extra physical stresses caused by waiting in temperatures of -30C, at an altitude where oxygen levels are not sufficient to sustain human life. Climbers call it “the death zone”.

But within the climbing community, people were less surprised. Last year’s was just a more extreme version of the bottlenecks that have been troubling the mountain with increasing frequency. The deaths were not caused by the queue itself, they argue, but a different problem: the rising numbers of inexperienced climbers who view Everest as the ultimate selfie destination, and the proliferation of companies willing to take their money and let them have a go, regardless of their ability.

‘Climbers don’t know the risks and aren’t concerned with them,’ says expedition leader Greg Vernovage, centre, with his team. Photograph: courtesy of Greg Vernovage

“There are people who call up and ask: ‘I’ve never climbed anything. Can I go with your company? And I need a discount,’” says Greg Vernovage, Everest expedition leader with International Mountain Guides, a well-established climbing firm. “Unfortunately, there is probably a company out there now that will take them. It’s very easy to jump on your computer and dig around for the lowest common denominator.”

Last year, 381 permits to climb the mountain were issued by the Nepalese government (a record number, 35 more than the previous year). The cost of climbing Everest varies wildly; cut-price operators will offer to take you up for as little as $30,000 (£24,600) – a price that includes the $11,000 (£9,000) permit – or you can pay $200,000 (£164,000) if you want to stay at the best hotels in the Nepalese capital of Kathmandu and be taken by the most experienced guides. Last autumn, Nepal’s Ministry of Tourism showed no sign of wanting to restrict the numbers of permits issued after last season, encouraging more people to come “for both pleasure and fame”.

There is suspicion that less well-established guides and companies find it harder to tell tourists they need to turn back if they see them struggling. “Just like a kid thinks they can eat a whole bag of candy without getting sick, climbers just want to stand on top. They don’t know the risks and they aren’t concerned with them,” Vernovage says. “Companies need to be a bit more forceful with clients. Just because you pay the money, that doesn’t give you a ticket to be on the summit team. I’ve had that difficult conversation with people.”

The cheaper firms have fewer backup staff, lower supplies of spare oxygen and less ability to manage things when dangerous situations arise. Purja, who runs his own climbing company, attributes the higher number of deaths in 2019 not so much to the numbers on the mountain as to the growth of cheaper operators, who employ less experienced guides. “We have backup people to help clients who are struggling. If everyone had been climbing with that support, no one would have struggled.”

Four Indian climbers were among the dead last year, leading to speculation that lower average salaries in India result in these climbers choosing cheaper tour operators, with tragic consequences. Attempting the mountain is expensive, so climbers are sometimes older, at the end of their careers, with expendable income but less physical stamina.

I saw people take 14 hours to cover a distance that took me two – people who usually have nothing to do with mountains

There has been no climbing season this year. The view from the ground has been spectacular: the disappearance of a pollution haze means the snow-capped peaks of Everest have been visible from Kathmandu for the first time in decades. But the only people on the mountain are a small group of Chinese researchers and surveyors – there to place 5G masts, and to mark the 60th anniversary of the first Chinese ascent of the north side of the mountain.

On 13 March, Nepal’s government locked down Everest, announcing that no climbing would be allowed on the mountain because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Police have patrolled the roads nearby to prevent anyone approaching. The cooks, porters and guides who help international tourists attempt the summit have mostly returned to their villages. With the disappearance of a year’s income, many have been pushed into destitution; a number of climbers have launched fundraisers to help Everest workers feed themselves and their families.

“I’m doing fine, I’m in England, I’ve managed to get income from my book,” Purja says. “But the community there is suffering. Some people don’t even have food to put on the table. It’s the saddest thing.”

***

David Göttler is a German climber who attempted the summit last May. As soon as he saw the queues at the top, he understood he was going to have to turn around. He was making an entirely self-sufficient attempt to summit, carrying his own kit and without oxygen – the most intensely challenging way to climb the mountain. “There are only a tiny fraction of people who can climb without oxygen,” he says. He views its use as a form of cheating, “like doping, like an enhancing drug”. But without oxygen, it was too risky to wait in line. He abandoned his climb around 100 vertical metres from the summit. It wasn’t the crowds that surprised him: “You don’t go to Everest for a lonely adventure,” he says. But he was dismayed by the slowness of the people ahead of him.

“I saw people who took 14 hours to cover a distance that took me two hours – these are people who usually have nothing to do with mountains. I have the feeling that they hear Everest is a nice thing to do and say: ‘Let’s do it!’”

David Göttler, who was climbing without oxygen and had to turn back because of the queues

FacebookTwitterPinterest

‘Most of these deaths were predictable,’ says David Göttler, who was climbing without oxygen and had to turn back because of the queues. Photograph: David Göttler

It was this inexperience that caused the spike in deaths, he says. “I don’t want to sound hard or without feelings, because it’s a tragedy for the families, but most of these deaths were predictable. It is surprising that there are not more of them, given how unprepared and naive people are. They pay the money and hire an agency, and think that this is a summit guarantee.”

Elia Saikaly, a Canadian film-maker, was on Everest last year to make a documentary about a team of four women from Saudi Arabia, Oman and Lebanon. Like Göttler, they made their ascent the day after Purja’s photograph was taken, when the queues were still long. Saikaly had attempted Everest many times before, and succeeded on two earlier occasions. But he remains troubled by what he saw that day; he is now making a film about how his attitude to the mountain was changed by his experiences.

There were between 25 and 40 people on and around the summit when Saikaly arrived at the tiny plateau at the top, a patch of mountain not much bigger than the surface area of a couple of ping-pong tables. He felt subdued as he arrived there. “I didn’t want anything to do with it, to be honest. Summits can be a bit of a disappointment, when you see that number of people taking selfies in such a spiritual place,” Saikaly says. “It wasn’t the pure experience it once was. The loss of life is very challenging. It makes you question why people do this and why you are there. We celebrated quietly.”

Becker also had mixed feelings as he stood at the peak, contemplating his achievement. “There wasn’t an ‘I found God’ moment at the top that some people say they have. I was torn,” he says. “I’ve dreamed about climbing it since I was a kid. But I think the 13-year-old me would have found it upsetting to go to the mountain and see it like that.”

Becker says he felt alienated by the “almost colonialist culture of must-conquer-the-mountains”. Some of his fellow climbers had already conquered figurative mountains in their business careers. “They think, because of that, they can conquer the mountain. There are people who paid six figures to get to the top and so they think: ‘I’m going to get my money’s worth. I must make it to the top of the mountain, who cares what happens?’ I think it draws certain people who will be happy to go to the top, at almost any cost to themselves and others.”

As well as this nagging ambivalence, Becker was in physical difficulty: his attempts to ration his depleted oxygen supply had led to his tank freezing; his mask had frozen on to his face and beard, the condensation inside it creating a cascade of ice down his front; his goggles were frozen to his suit. Without goggles, he was worried about developing ice blindness in the glare of the sun on the descent.

US guide Garrett Madison on Everest with flags and other climbers behind him

FacebookTwitterPinterest

‘It can be a good reality check; it reinforces the gravity of it all,’ says US guide Garrett Madison of seeing dead climbers. Photograph: courtesy of Garrett Madison

Most of all he, like other climbers on Everest last year, was very shaken by the experience of having to walk past so many dead climbers. Garrett Madison, a US guide who was climbing with Saikaly, says it is something climbers see every year, but remains hard to get used to. “For a first-time climber, it can be shocking,” he says. “It can be a good reality check; it reinforces the gravity of it all.”

Conditions are so harsh at the summit that it is usually impossible to expend energy on carrying bodies back. “It is a major effort to bring a corpse down,” Madison says. “It is not like you can just chuck them on your back and trot on down.”

Becker was unable to avert his eyes. “The first person had the same boots as me, the same scrawny build as me. It was scary – he looked like me. I imagined myself in that situation, and I very much did not want to be in that situation. I was just sad for this guy. I thought about his family – does he have kids or a wife, or parents? What are they going to think?”

Worse was a sense that some seemed unconsciously to revel in the danger. “I’m not saying that anyone saw a dead body and thought: ‘Oh, this is great!’” he says. “There were some people who seemed upset about it. But there were others whose attitude was – and I’m speculating – ‘Wow, this is such a dangerous mountain, and I made it!’ It almost made it more romantic that they made it to the top despite these deaths. That attitude was pretty uncomfortable.”

***

In the wake of last year’s queues, there has been renewed discussion in Nepal about how better regulation of firms and climbers could be introduced. Some trekking firms would like firmer control of how many climbers can attempt the summit on a given day. A government panel recommended that anyone applying for a permit must in future show that they have successfully completed a 6,500 metre (21,325ft) climb, but the proposals had not been implemented before Covid-19 prompted lockdown. The damage caused to the country’s tourist industry may have reduced the willingness to regulate.

This April, a team of Nepalese soldiers had been due to mount an expedition to remove the mess that has been accumulating on the mountain for years: piles of empty fuel canisters, tents (the climbing company’s logo carefully cut out before they were abandoned, to avoid responsibility), food wrappers and human excrement. But when climbing permits were cancelled, the cleanup operation was also abandoned.

Last year there was a line of people quite literally dying because of the over-commercialisation of the mountain

No one is sure whether the crowds will return next year. Most climbers who were forced to cancel trips this spring would like to return in 2021, which means the queues could be heavier still, with two years’ worth of tourists attempting to summit at once. But if there is a global economic slump, fewer people will have the spare money to fund this very expensive adventure travel.

Purja hopes that climbers will come back, to restore the livelihoods of the Nepalese climbing community, but he also hopes the next season will be cleaner and less chaotic. Other climbers say last year’s season has made them re-evaluate their attitude to Everest.

“Last year there was a line of people quite literally dying because of the over-commercialisation of the mountain,” Becker says. “People have come to think, if you throw money at it you can get to the top, which brings more inexperienced people to the mountain and more sherpas to work there. It does make me reflect on what kind of climbing I want to do, what’s responsible and doesn’t endanger myself and others. And to think about whether I am perpetuating this culture – the romanticisation of Everest. I worry that, am I in some way part of the problem?”Purja's original photo-

-

2

2

-

-

3 minutes ago, Josef Svejk said:

The BBC and other parts of the British media continue to lie about the death figures here. And even those figures are buried under speculative / circumstantial stories about a long-missing girl. Next step: just stop reporting the figures altogether...

They already have in one respect- the figure for number of people tested has been 'unavailable' for about two weeks now.

Coronavirus

in GF - General Forum

Posted

I'm starting to wonder if the outbreak actually occurred in Stenhousemuir. The hospital car park there was half empty when I went for an out patient's appointment in March; at the repeat in October, it was fucking rammed and I had to park miles away. Not definitive proof, but deeply suspicious.